- Paper should be @ 8 pages, double spaced Times New Roman, Microsoft Word format

- You MUST give proper citations for anything that is not your own thought, or else it will be considered plagiarism. Include a Bibliography, if necessary.

- Please limit your references to works of art and architecture that we have already discusssed in class. The point of this assignment is not to break new ground but to make connections and concretize what you have already learned.

- You may submit them to me online, BUT BE SURE TO MAIL THEM TO THIS ADDRESS: bethb@valleycovenant.org

- Papers MUST be received by 1 pm, Dec. 16, 2010 in order to receive full credit.

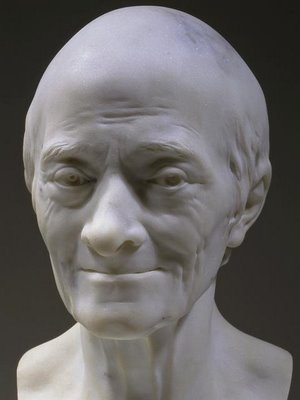

1. Trace the impact of Greek art and thought on Western art and architecture from Rome through the 19th century, by discussing at least five specific examples in detail.

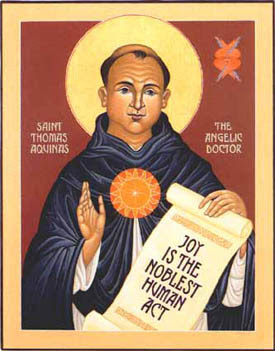

2. Discuss how Western art and architecture can be understood in terms of “ping- ponging” between the ideal and the real, the head and the heart, etc. (as presented in the class handout, “Two Aspects of being Human.”) Discuss at least five specific examples in detail.

3. The thought of the modern period (17th – 19th century) has been described as “the eclipse of God.” What is meant by this? Show how this “eclipse” was captured in Western art and architecture by discussing at least five specific works and/or buildings in detail. In your opinion, which period and style do you think most successfully exhibits the Christian worldview? Why?

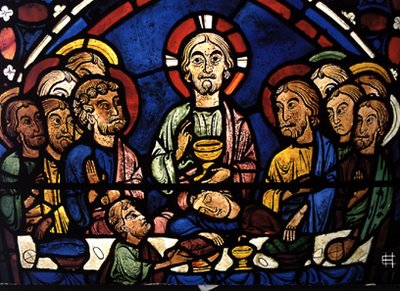

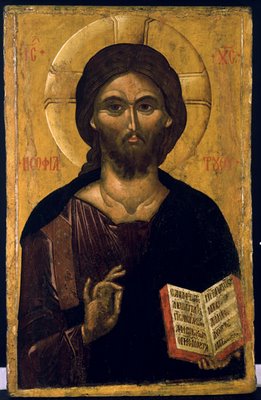

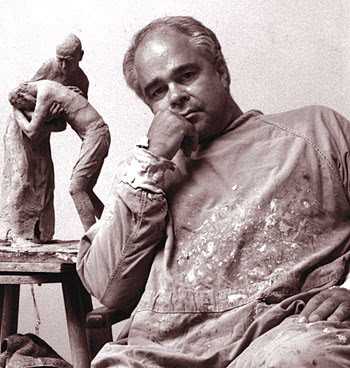

4. Discuss the relations of paintings, sculpture and architecture to the Church, from the 1st-19th century, by analyzing at least five select works. In your opinion, has Christian worship been enriched or diminished by images? Why? Which period and style do you think most successfully captures the Christian worldview? Why?