by George Herbert

Lord, how can man preach thy eternal word?

He is a brittle crazy glass;

Yet in thy temple thou dost him afford

This glorious and transcendent place,

To be a window, through thy grace.

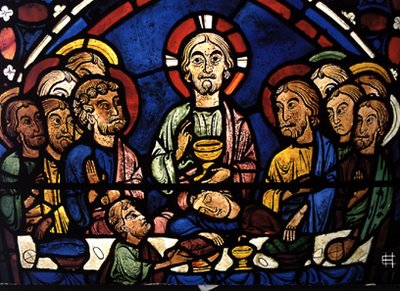

But when thou dost anneal in glass thy story,

Making thy life to shine within

The holy preachers, then the light and glory

More reverend grows, and more doth win;

Which else shows waterish, bleak, and thin.

Doctrine and life, colors and light, in one

When they combine and mingle, bring

A strong regard and awe; but speech alone

Doth vanish like a flaring thing,

And in the ear, not conscience, ring.

NOTE: Anneal is a term that means to use great heat to actually burn colors into the glass.

Thursday, October 21, 2010

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

PREPARATION for Test #3: Middle Ages

The test on Monday will cover the early, high and late middle ages. That means chapters 9, 10 and 11, with the EXCEPTION of the following sections:

Chapter 9:

Monasticism and Gregorian Chant

Liturgical Music and the Rise of Drama

The Morality Play

The Legend of Charlemagne: Song of Roland

Chapter 10:

Music: The school of Notre Dame

Dante's Divine Commedy

Chapter 11:

Literature in Italy, England and France

Music: Ars Nova

Define:

ambulatory

mendicant

lancet

archivolt

tympanum

flying buttress (also called "flying arch")

horarium

scriptorium

Seven Liberal Arts

trivium

quadrivium

dialectic

Scholasticism

Sic et Non

“Credo ut Intellegam”

hierarchy

Rule of St. Benedict

Carolingian miniscule

"Gothic"

Lectio Divina

"mysticism of light"

narthex

nave

pilgrimage church

relics

Black Death

Hundred Year’s War

Great Schism

Nominalism

“Devotio Moderna”

Giotto

Duccio

International Gothic Style

duomo

perpendicular

Explain who or what these are, and why they are important:

Charlemagne

Alcuin

Saint Sernin, Toulouse Church (be able to identify)

Chartres Cathedral (Be able to identify)

Beauvais Cathedral

Milan Cathedral (Duomo, Milan) (Be able to identify)

Palace at Aachen (be able to identify)

Paris (the city of)

University of Paris

Abbot Suger

St. Benedict of Nursia

St. Francis of Assisi

St. Thomas Aquinas

Dominicans

Franciscans

Benedictines

Rule of St. Benedict

Scholasticism

Dagulf Psalter (identify)

Summa Theologiae

Wilton Diptych (identify)

Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (identify)

Discuss:

(refer to readings and power point presentations)

· How did Charlemagne and Alcuin foster literacy and learning?

· Identify and discuss the Utrecht psalter, the Dagulf Psalter and the Gospel book of Charlemagne

· Who were the important philosophers of the early and high middle ages, and what were some of their ideas?

· What is meant by Scholasticism?

· Discuss the Romanesque style. How does it reflect Benedictine traditions? Discuss some specific Romanesque buildings.

· Discuss the Gothic style How does it reflect Scholasticism? Discuss some specific Gothic cathedrals.

· Compare and contrast Romanesque and Gothic architecture.

· What is meant by “the mysticism of light?” Give examples.

· What is meant by the term “gothic?”

· What three factors made the 14th century a “time of transition?” What effect did they have on the way people of the late middle ages thought and valued? How did this play out in the art and architecture of the time?

· Are there any similarities between the world of the 14th century and ours today? Explain.

· Explain how the Black Death, the Great Schism, and the Hundred Years’ war changed European culture

· Explain the importance of these cities: Paris, Siena

· Why is Giotto important? What is meant by his "break with the past?"What are the important themes of the Middle Ages? Discuss in detail.

· Explain, and give examples of how the medievals understood life as a pilgrimage.

· Explain and discuss the "both-and" worldview of the middle ages.

· What was the impact of Monasticism on the middle ages?

Compare and contrast St. Francis and St. Thomas Aquinas

OPTIONAL: The Slippery Slope of Nominalism

Nominalism --> voluntarism--> Luther and Calvin --> Kierkegaard -->; Nietzsche -->Sartre

--> Postmodernism

What is Nominalism? (or, the story of some "isms")

Premoderns were metaphysical realists, either extreme (Platonists) or moderate (Aristotelians).

Realists think there are “forms,” natures or essences, which exist independent of human minds. These natures, or essences are also called universals. Platonists thought those forms existed in a separate, transcendent realm: the Ideal world, as opposed to the material world. Aristotelians thought that (for the most part, with only a few exceptions) the forms existed in this world. Moderate realists hold that there is no separate realm in which universals exist, but rather universals are located in space and time, in things themselves. Yet even though they might not exist in a separate world, these universals, or essences still are abstractions, or meta-physical entities, things which are known by the intellect, and not by the senses.

At the end of the middle ages, in the 14th century, an entirely new idea arrived, and one might consider it the death knell of premodernism and the birth of modernism. Nominalism is the view that there are no universals, and thus no essences. Nominalists hold that various objects labeled by the same term have nothing in common but their name. In contrast to Platonic realism ( which held that universals have a separate existence apart from the individual object) nominalism insists that reality is found only in the objects themselves, not in any meta-physical realm or principle. Thus the senses increasingly became the vehicle for deciding what is real.

For us today, comfortable as we are with scientific naturalism and a materialistic view of reality, none of this sounds very revolutionary. But consider the implications for premodern persons. “If there are no universals, then things are radically individualized” the premodern protests. “There is no way for things to be connected. Everything is autonomous.” Nominalism required a 180 degree intellectual shift for the medieval premodern mind, which had not hesitated to make distinctions between things, but did so in order to unite them ultimately in a great chain of being created by, sustained by, and redeemed by God:

“Philosophy is to distinguish (Philosophiae est distinguere). But its ultimate purpose is not to decompose things into fragments, but to appreciate more profoundly the diversity within unity, the multi-faceted constitution of being, the manner in which the object of philosophical inquiry is integrated.” http://www.cfpeople.org/Apologetics/page51a054.html

Nominalist thinkers did just the opposite. The revolution was led by William of Ockham and Francis Bacon. Holding things to be radically separate, nominalists like Ockham sought to impose some sort of order on the chaos, by grouping things together according to the needs and uses of the person knowing them. Rather than submitting and conforming one’s mind to reality one’s mind begins to actively shape reality.

The Nominalists agenda was also furthered by Francis Bacon’s new emphasis on knowing by induction rather than by deductive syllogism. Because the senses always only encounter individual particulars, they become the starting point for any sort of “objective,” factual knowing. Universals, abstractions, and other meta-physical items thus can never be known “objectively,” as facts, because they can never be immediately known through the senses. They can only be known subjectively, as matters of ‘belief.” Belief in turn becomes accepted as purely a matter of will, and so the stage is set for a voluntaristic God—a sovereign God whose essence is Will—and Who is the object faith, not reason.

“In the fourteenth century William of Ockham devised a nominalistic system of theology based on his belief that universals were only a convenience of the human mind. According to this view, the fact of a resemblance between two individuals does not necessitate a common attribute; the universals one forms in his mind more likely reflect one's own purposes rather than the character of reality. This led William to question scholastic arguments built upon such abstractions. As he argues in his Centilogium, systematization of theology must be rejected, for theology can ultimately be based only on faith and not on fact. Therefore, through grace and not knowledge, he accepted the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, bowed to the authority of the pope, and declared the authority of Scripture. His follower, Gabriel Biel, would carry his thought to its logical conclusion and declare that reason could neither demonstrate that God was the First Cause of the universe nor make a distinction between the attributes of God, including God's intellect and will. The reality of the Trinity, as well as any theological dogma, can be found only in the realm of faith, not in the realm of reason. This was diametrically opposed to the natural theology of medieval scholasticism.”

(the above is taken from http://mb-soft.com/believe/txn/nominali.htm. For more about this transition, also see http://ic.net/~erasmus/RAZ229.HTM “The Influence of William of Ockham and Nominalism on Martin Luther and Early Protestant Thought,” compiled and edited by Dave Armstrong.)

Once immaterial, spiritual things are consigned to the realm of belief, not fact, they are forced to be objects of will, not reason. Kierkegaard sees this clearly, and fully embraces it, calling for the “leap of faith.” Nietzsche-- building upon Kant’s idea that all we can know are appearances (phenomena) never the reality (noumena)—further develops the significance of the will by insisting reality is the creation of the person with the most powerful will, the “ubermensch,” or “super-man.” Sartre can be seen as a kinder, gentler Nietzsche, whose mantra, “existence comes before essence” also underscores the superiority of will. For Sartre, I progressively define myself (and my reality) by my choices.

Philosophical postmodernism is the celebration of subjectivity, and the denial of any objective metaphysical, epistemological or moral absolutes, for “absolutes” are universal, and if there is nothing universal, then there is nothing absolute. It is no wonder, then, that Christians like Rodney Clapp ( A Peculiar People: The Church as Culture in Postmodern Society, InterVarsity, 1996) argue that philosophical Postmodernism can be seen as the final stage of modernist nominalism. It will be interesting to see how Protestantism, having been birthed by nominalism, extricates itself from nominalism’s suffocating grip.

OPTIONAL: Bernard of Clairvaux, Medieval Hymnist

These songs of worship were written by Bernard of Clairvaux in the 12th century. Click on the first line link for the tune.

Jesus, the very thought of Thee

With sweetness fills the breast;

But sweeter far Thy face to see,

And in Thy presence rest.

Nor voice can sing, nor heart can frame,

Nor can the memory find

A sweeter sound than Thy blest Name,

O Savior of mankind!

O hope of every contrite heart,

O joy of all the meek,

To those who fall, how kind Thou art!

How good to those who seek!

But what to those who find? Ah, this

Nor tongue nor pen can show;

The love of Jesus, what it is,

None but His loved ones know.

Jesus, our only joy be Thou,

As Thou our prize will be;

Jesus be Thou our glory now,

And through eternity.

O Jesus, King most wonderful

Thou Conqueror renowned,

Thou sweetness most ineffable

In Whom all joys are found!

When once Thou visitest the heart,

Then truth begins to shine,

Then earthly vanities depart,

Then kindles love divine.

O Jesus, light of all below,

Thou fount of living fire,

Surpassing all the joys we know,

And all we can desire.

Jesus, may all confess Thy Name,

Thy wondrous love adore,

And, seeking Thee, themselves inflame

To seek Thee more and more.

Thee, Jesus, may our voices bless,

Thee may we love alone,

And ever in our lives express

The image of Thine own.

O Jesus, Thou the beauty art

Of angel worlds above;

Thy Name is music to the heart,

Inflaming it with love.

Celestial Sweetness unalloyed,

Who eat Thee hunger still;

Who drink of Thee still feel a void

Which only Thou canst fill.

O most sweet Jesus, hear the sighs

Which unto Thee we send;

To Thee our inmost spirit cries;

To Thee our prayers ascend.

Abide with us, and let Thy light

Shine, Lord, on every heart;

Dispel the darkness of our night;

And joy to all impart.

Jesus, our love and joy to Thee,

The virgin’s holy Son,

All might and praise and glory be,

While endless ages run.

Jesus, Thou Joy of loving hearts,Thou Fount of life, Thou Light of men,

From the best bliss that earth imparts,

We turn unfilled to Thee again.

Thy truth unchanged hath ever stood;

Thou savest those that on Thee call;

To them that seek Thee Thou art good,

To them that find Thee all in all.

We taste Thee, O Thou living Bread,

And long to feast upon Thee still;

We drink of Thee, the Fountainhead,

And thirst our souls from Thee to fill.

Our restless spirits yearn for Thee,

Wherever our changeful lot is cast;

Glad when Thy gracious smile we see,

Blessed when our faith can hold Thee fast.

O Jesus, ever with us stay,

Make all our moments calm and bright;

Chase the dark night of sin away,

Shed over the world Thy holy light.

OPTIONAL: Medievals, Moderns (and Postmoderns) on Heaven

If you haven't discovered Peter Kreeft, now is the time. Here is one of his articles from his website.

What Difference Does Heaven Make?

If a thing makes no difference, it is a waste of time to think about it. We should begin, then, with the question, What difference does Heaven make to earth, to now, to our lives?

Only the difference between hope and despair in the end, between two totally different visions of life; between "chance or the dance". At death we find out which vision is true: does it all go down the drain in the end, or are all the loose threads finally tied together into a gloriously perfect tapestry? Do the tangled paths through the forest of life lead to the golden castle or over the cliff and into the abyss? Is death a door or a hole?

To medieval Christendom, it was the world beyond the world that made all the difference in the world to this world. The Heaven beyond the sun made the earth "under the sun" something more than "vanity of vanities". Earth was Heaven's womb, Heaven's nursery, Heaven's dress rehearsal. Heaven was the meaning of the earth. Nietzsche had not yet popularized the serpent's tempting alternative: "You are the meaning of the earth." Kant had not yet disseminated "the poison of subjectivism" by his "Copernican revolution in philosophy", in which the human mind does not discover truth but makes it, like the divine mind.

Descartes had not yet replaced the divine I AM with the human "I think, therefore I am" as the "Archimedean point", had not yet replaced theocentrism with anthropocentrism. Medieval man was still his Father's child, however prodigal, and his world was meaningful because it was "my Father's world" and he believed his Father's promise to take him home after death.

This confidence towards death gave him a confidence towards life, for life's road led somewhere. The Heavenly mansion at the end of the earthly pilgrimage made a tremendous difference to the road itself. Signs and images of Heavenly glory were strewn all over his earthly path. The "signs" were (1) nature and (2) Scripture, God's two books, (3) general providence, and (4) special miracles. (The word translated "miracle" in the New Testament [sëmeion] literally means "sign".) The images surrounded him like the hills surrounding the Holy City. They, too, pointed to Heaven. For instance, the images of saints in medieval statuary were seen not merely as material images of the human but as human images of the divine, windows onto God. They were not merely stone shaped into men and women but men and women shaped into gods and goddesses. Lesser images too were designed to reflect Heavenly glory: kings and queens, heraldry and courtesy and ceremony, authority and obedience—these were not just practical socio-economic inventions but steps in the Cosmic Dance, links in the Great Chain of Being, rungs on Jacob's ladder, earthly reflections of Heaven. Distinctively premodern words like glory, majesty, splendor, triumph, awe, honor—these were more than words; they were lived experiences. More, they were experienced realities.

The glory has departed. We moderns have lost much of medieval Christendom's faith in Heaven because we have lost its hope of Heaven, and we have lost its hope of Heaven because we have lost its love of Heaven. And we have lost its love of Heaven because we have lost its sense of Heavenly glory.

Medieval imagery (which is almost totally biblical imagery) of light, jewels, stars, candles, trumpets, and angels no longer fits our ranch-style, supermarket world. Pathetic modern substitutes of fluffy clouds, sexless cherubs, harps and metal halos (not halos of light) presided over by a stuffy divine Chairman of the Bored are a joke, not a glory. Even more modern, more up-to-date substitutes—Heaven as a comfortable feeling of peace and kindness, sweetness and light, and God as a vague grandfatherly benevolence, a senile philanthropist—are even more insipid.

Our pictures of Heaven simply do not move us; they are not moving pictures. It is this aesthetic failure rather than intellectual or moral failures in our pictures of Heaven and of God that threatens faith most potently today. Our pictures of Heaven are dull, platitudinous and syrupy; therefore, so is our faith, our hope, and our love of Heaven.

It is surely a Satanic triumph of the first order to have taken the fascination out of a doctrine that must be either a fascinating lie or a fascinating fact. Even if people think of Heaven as a fascinating lie, they are at least fascinated with it, and that can spur further thinking, which can lead to belief. But if it's dull, it doesn't matter whether it's a dull lie or a dull truth. Dullness, not doubt, is the strongest enemy of faith, just as indifference, not hate, is the strongest enemy of love.

It is Heaven and Hell that put bite into the Christian vision of life on earth, just as playing for high stakes puts bite into a game or a war or a courtship. Hell is part of the vision too: the height of the mountain is appreciated from the depth of the valley, and for winning to be high drama, losing must be possible. For salvation to be "good news", there must be "bad news" to be saved from. If all of life's roads lead to the same place, it makes no ultimate difference which road we choose. But if they lead to opposite places, to infinite bliss or infinite misery, unimaginable glory or unimaginable tragedy, if the spirit has roads as really and objectively different as the body's roads and the mind's roads, and if these roads lead to destinations as really and objectively different as two different cities or two different mathematical conclusions—why, then life is a life-or-death affair, a razor's edge, and our choice of roads is infinitely important.

We no longer live habitually in this medieval mental landscape. If we are typically modern, we live in ennui; we are bored, jaded, cynical, flat, and burnt out. When the skies roll back like a scroll and the angelic trump sounds, many will simply yawn and say, "Pretty good special effects, but the plot's too traditional." If we were not so bored and empty, we would not have to stimulate ourselves with increasing dosages of sex and violence—or just constant busyness. Here we are in the most fantastic fun and games factory ever invented—modern technological society—and we are bored, like a spoiled rich kid in a mansion surrounded by a thousand expensive toys. Medieval people by comparison were like peasants in toyless hovels—and they were fascinated. Occasions for awe and wonder seemed to abound: birth and death and love and light and darkness and wind and sea and fire and sunrise and star and tree and bird and human mind—and God and Heaven. But all these things have not changed, we have. The universe has not become empty and we, full; it has remained full and we have become empty, insensitive to its fullness, cold hearted.

Yet even in this cold heart a strange fire kindles at times—something from another dimension, another kind of excitement—when we dare to open the issue of Heaven, the issue of meeting God, with the mind and heart together. Like Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones, we experience the shock of the dead coming to life.

C.S. Lewis: "You have had a shock like that before, in connection with smaller matters—when the line pulls at your hand, when something breathes beside you in the darkness. So here; the shock comes at the precise moment when the thrill of life is communicated to us along the clue we have been following. It is always shocking to meet life where we thought we were alone. "Look out!" we cry, "It's alive!" And therefore this is the very point at which so many draw back—I would have done so myself if I could—and proceed no further with Christianity. An "impersonal God"—well and good. A subjective God of beauty, truth and goodness inside our own heads—better still. A formless life-force surging through us, a vast power that we can tap-best of all. But God Himself, alive, pulling at the other end of the cord, perhaps approaching at an infinite speed, the hunter, king, husband—that is quite another matter. There comes a moment when the children who have been playing at burglars hush suddenly: was that a real footstep in the hall? There comes a moment when people who have been dabbling in religion ("Man's search for God"!) suddenly draw back. Supposing we really found Him? We never meant it to come to that!"

When it does come to that, we feel a strange burning in the heart, like the disciples on the road to Emmaeus. Ancient, sleeping hopes and fears rise like giants from their graves. The horizons of our comfortable little four-dimensional universe crack, and over them arises an enormous bliss and its equally enormous absence. Heaven and Hell—suppose, just suppose it were really, really true! What difference would that make?

I think we know.

From Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Heavenby Ignatius Press.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)